The goal: to track down the person who made one Huskies sweatshirt, in hopes of narrowing the gap between U.S. consumers and the lives of garment workers.

Anissa folds back the cuff of the purple Huskies hoodie, and runs a finger over the inside stitches.

In the brief moment she holds the sweatshirt, her expression flashes from smiling twenty-four year-old to engaged professional and back again.

The deftness of her inspection hints at her skill as a seamstress who handles 120 of these sweatshirts every hour at the factory where she works.

The shirt, bearing quarterback Keith Price’s number 17, was on discount at The University Bookstore on “The Ave” in Seattle.

In July it made its homecoming via yellow DHL shipping bag to here, where it was made.

My goal was to track down the person who made it, in the hope of highlighting her connection with consumers in Seattle and the clothes on our retail store racks.

With over 1.3 million garment workers in Indonesia, it sounded like a needle in a haystack.

But thanks to transparency tools on Nike’s manufacturing web site and a local labor-union connection, in less than 48 hours I was sitting in Jakarta traffic on my way to a meeting with a group of garment workers in the city’s north east end.

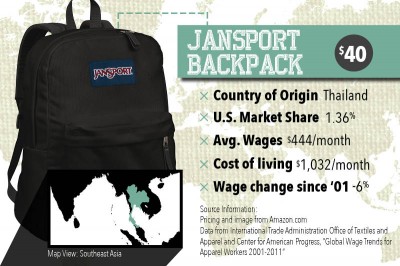

Where did your back to school gear come from?

The Nike website narrowed the search down to 10,734 workers producing collegiate apparel at six factories, five of which are in the sprawling outskirts of this city of over 10 million.

Sitting still in Jakarta’s notorious gridlock it crossed my mind that this was probably the second time the hoodie had been subjected to this traffic.

As the slow creep continued out of the city center, curbs receded to gutterless one-lane roads full of more motorbikes than cars. Food stalls lined the road against a backdrop of concrete homes and the occasional rice field.

We reached a neighborhood where the streets were lined with mannequins stuffed into stretch pants. Open doors exposed teams of people on sewing machines; we were getting close.

Before long I was sitting on the tiled floor of a stucco house with Anissa, who, like all the factory workers in this story, asked that their real names not be used for fear of losing their jobs.

Anissa’s husband and another couple who worked in a different factory sat on the floor next to us along with a few union leaders.

They probably weren’t big Husky football fans, but everyone in the room knew the sweatshirt well.

One of the men from the union had recognized the shirt’s material from a visit to the factory where Anissa worked. The second couple remembered attaching the numbers to the shirt. And Anissa remembered sewing its cuffs.

Cheap clothes vs. consumer conscience

Anissa and her coworkers are part of the most recent generation in a long line of Indonesians who have worked for apparel and footwear companies — sometimes under questionable conditions.

Their country has long played a significant if not dominant role in clothing production. It is now the third largest source of apparel exports to the US by dollar value, and manufactures about six-and-a-half percent of our clothing imports. Globally, the Southeast Asian nation has been amongst the top ten apparel exporters since the 1980s. In 2000 its apparel exports were around two-and-a-half percent of global output.

Around the same time that Indonesia became one of the world’s top exporters of garments, a flood of reports and articles on Nike’s labor practices in Indonesia forever linked the company to the term ‘sweatshop.’

Across the apparel industry, celebrities like Kathy Lee Gifford and even Michael Jordan were embarrassed when the public found out that apparel bearing their names was produced using sweatshop labor.

The negative publicity moved Portland-based Nike and many of its competitors to create codes of conduct for their subcontracted factories. But public interest in the issue subsided as aggressive outsourcing became the norm for manufactured goods.

That is until April of this year, when the deadliest accident in the history of the garment industry hit Bangladesh. A factory collapse near Dhaka killed more than a thousand people and put working conditions of businesses involved in globalized manufacturing back in the spotlight.

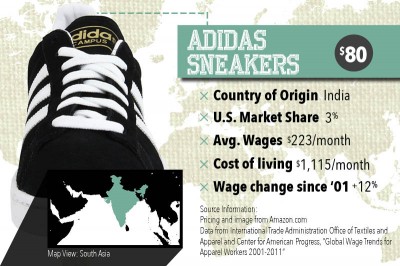

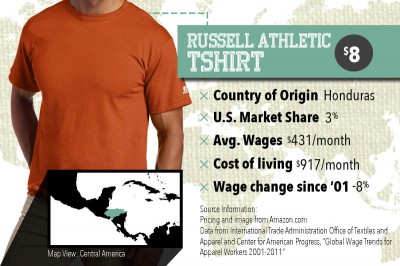

A subsequent study of the industry by the Center for American Progress found that between 2001 and 2011 the real wages of garment workers in the U.S.’ main source countries had been, for the most part, falling.

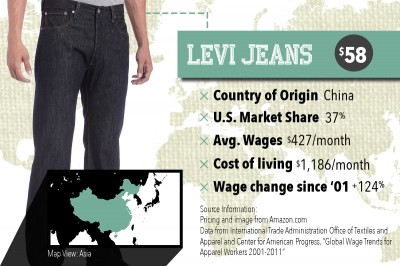

The big exception over that period was top exporter China, which has seen real wages expand by 124 percent.

In the years leading up to the Bangladesh disaster, China, which produced 40% of U.S. apparel imports over the last decade, was starting to price itself out of the business. Companies had been looking to take their production to countries with lower wages and none looked better than Bangladesh.

In a 2011 report by McKinsey Quarterly titled “Bangladesh: the Next Hot Spot in Apparel Sourcing?” chief purchasing officers from top apparel companies cited the appeal of an already established garment industry, a huge work force, and extremely low minimum wages.

But since the factory collapse and the numerous smaller tragedies that came both before and after the disaster, there has been a new trend in manufacturing that stands out above the rest: staying as far away from Bangladesh as possible.

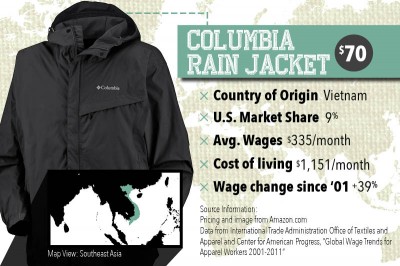

A May New York Times article described an urgent hunt by Western executives to find alternative locations for production. High on their list were a number of Southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia.

A race to the bottom

You could be forgiven for thinking Anissa is a teenager. She’s full of the youthful energy and has a high pitched laugh that never seems far away.

When I ask her about her job, she gives measured answers. She doesn’t want to complain.

Anissa has worked at P.T. Greentex for two years. When I put the hoodie down in front of her, her eyes light up.

“This is my labor, I’m proud,” she says confidently when I ask her how seeing the completed shirt makes her feel.

Her days start early at the factory. She works from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. Once a week she’ll take an hour of overtime and leave around 5.

Her husband Wayan is concerned about her working during her pregnancy. She’s three months along and has already fainted once while on the job. The problem is they need the money, and she says she would just be bored staying at home.

To be honest, I was surprised by her responses when I asked about conditions in the factory where she works. I expected echoes of the cracked walls, locked doors and shoddily placed generators that lead to the Bangladesh disaster.

Instead she says her boss is not threatening. No one under 17 is allowed to work in the factory. The facilities, while far from perfect, feel safe.

There’s no way for me to see for myself. Like most factories in Indonesia, access is strictly guarded, so I’m in no position to question Anissa’s take on her workplace.

But if conditions in the factory are acceptable, I can’t understand why the workers seem to be hinting at some sort of major problems, or why they didn’t want me to use their real names.

When I bring up the cost of the sweatshirt in the US, the positive tone shifts and it starts to become clear.

The sweatshirt was marked down to $30, but there is a conspicuous tag attached to the it showing the original price: $75. When I explain the amount the room fills with the laughter. But it’s not happy laughter. It’s the kind you resort to when you know getting angry will just be a waste of energy.

Anissa and her coworkers live off a salary of 1.9 million rupiah, or about $190 every month. A single sweatshirt, one of which Anissa’s line is supposed to sew roughly every 30 seconds, costs about 39 percent of her monthly wage.

Of course, just because workers are paid pennies to produce a garment that retails for $75, doesn’t mean Nike is pocketing the difference. PT Greentex pays to keep the factory running and takes its cut, then there’s the cost of shipping to Seattle, licensing fees the University of Washington collects on Husky merchandise, and a retail markup by the store of as much as 100 percent.

Still, a country by country analysis by the Center for American Progress found that prevailing wages in the garment industry were a fraction of a realistic living wage for a family of four with two breadwinners, Even in countries like China and Indonesia where wages are on the rise, it will be decades before the prevailing wage is enough to support basic needs like food, housing, health care and education.

I ask Anissa if her salary is enough to live on and again she’s careful not to complain.

“Yes, maybe it’s enough for now, because we don’t have children,” she says, laughing nervously.

Increasing wages

Low wages and the factory’s high output gets to the marrow of what is one of Indonesia’s thorniest issues of the day.

Over the last half-decade the country has performed, economically speaking, with the kind of consistency that Huskies fans would be thrilled to get out of Keith Price.

A strong middle class has emerged, and with it, so have demands from those at the bottom of the economic ladder for higher minimum wages. Long suppressed under former President Suharto, unions have become stronger forces ensuring that those demands reach the ears of business leaders and politicians.

The issue has become a political ball, run up the field by politicians looking for popular support, and back down by industry looking to keep its bottom-line in the cellar.

On paper some of the demands for increased wages have been met. Pressure from striking workers increased the minimum wage across the country 30 to 40 percent.

But that’s just on paper.

Anissa’s factory is in an area where the minimum wage for the garment sector was supposed to increase to 3.2 million rupiah (or about $320) per month starting last January. She and her coworkers say they haven’t yet seen an increase in wages, and that seems to be the trend around the city.

Tired of feeling guilty about buying clothes?

Jim Keady is one of many Americans who have devoted their lives to improving conditions for garment workers. Director of the New Jersey based Educating for Justice, he has been coming to Indonesia for close to 14 years to advocate for Nike workers. Keady is one of the prominent voices of the anti-sweatshop movement.

Last year helped secure $1 million dollar settlement for workers at the largest Nike factory in Indonesia for what he called an 18 year practice of forced unpaid over time. The unpaid hour of work was so common there was even an expression for it: the Jam Malor.

“Every Nike subcontractor has to commit to Nike’s code of conduct,” Keady says. “That code of conduct is very clear with regard to workers being paid at least the minimum wage in a country like Indonesia. Right now, that’s not happening.”

Officials of the Federasi Serikat Buruh Indonesia, which translates to The Indonesian Trade Union Federation, echo Keady’s statement that forcing manufacturers’ hands to pay minimum wages is one of their top priorities.

But Indonesian garment industry’s leaders argue that the new minimum wages hurt their ability to compete with every low-wage country on the planet. They fear jobs heading to even cheaper Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam, Cambodia, and Burma.

Industry Minister M.S. Hidayat told The Jakarta Post that as many as 900,000 workers could lose their jobs if the new minimum wages went into full effect.

“Businesses cannot bear the costs incurred by the new minimum wage,” he said, arguing that Indonesia’s reputation has been damaged by continued worker protests.

If they’re correct, that local moves to raise wages will only further a race to the bottom, the answer may come in the form of consumer advocacy.

Campus organization United Students Against Sweatshops is the preeminent U.S.- based group advocating for manufacturing workers in the developing world. This year student network successfully concluded a two-year campaign over severance pay at another Indonesian factory, PT Kizone, which ended in a major settlement to the workers.

The fight cost Adidas 17 contracts with major universities, including the University of Washington.

“I don’t know if [students] care more, but I’d say we’re more proactive and mobilized than the average consumer,” said Rachel Shevrin, a member of the University of Washington Chapter of United Students Against Sweatshops. “We’re part of a generation that thinks that is a human rights issue and we’re going to fix it.”

Last March, Nielsen Media Research profiled a new demographic of “global, socially conscious consumers” that savvy businesses should be targeting. Forty six percent of the consumers Nielsen surveyed in the US and around the world said that they’d be willing to pay more for products from companies that have taken steps to “give back to society” in some way.

But Jim Keady says consumers should go beyond just ‘voting with their wallets’.

“I think that consumers have responsibility to, one, be informed about the conditions under which the products that they’re buying are produced,” he said “If you feel a product is being made in a way that you don’t feel comfortable with, you need to contact Nike.”

University of California Berkeley professor Dara O’Rourke, the co-founder of GoodGuide which rates companies and products social responsibility, suggests that consumers should contact companies they don’t feel are up to an acceptable standard through public channels like Twitter.

She also encourages conscious consumers to avoid buying apparel manufactured overseas altogether by buying clothes secondhand or seeking out some of the few brands that are made domestically.

I ask the group if they want Americans to boycott their products in the name of better wages and working conditions. Anissa’s colleague speaks up first:

“Buy them, of course. If not, then most likely the company will go bankrupt.”

This is far from a battle cry in support for her employers —It’s more an acknowledgement that her wages depend on their continued sales to Nike, and on to American consumers. Not buying products in support of those who make them is a case of cutting off the nose to spite the face.

Anissa adds her two cents:

“If (Americans) buy them, we have work making them…there just needs to be balance in pay.”

Second Place Winner, Online Special Report, 2013 Society of Professional Journalists awards.

[ts_fab authorid=”70″ tabs=”bio”]

Thanks for an informative well written article!

Look at Indonesia’s population density growth. Something has to curb it.

https://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=en_pop_dnst&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=region&idim=country:IDN:MEX:USA&ifdim=region&tstart=-261162000000&tend=1316674800000&hl=en&dl=en&ind=false

Taiwan is not part of China. The living standards are totally different. Very misleading information.

The data set does not include Taiwan. Thanks for catching the mistake on the map. It’s been updated.

Great work! Thanks to everyone involved. This is the kind of journalism we need!

Excellent article that puts a Husky sweat-shirt that retails for $75 into the context of an Indonesian worker who made it, and who earns $190 per month. In Seattle terms, that is enough to buy 2 1/2 shirts. Thank you to Branden Eastwood for this educational expose.

Great piece of information all American consumers need to see.

Great article and especially informative about the issue of whether or not to boycott or not buy the products.

Great article. Good to see you go to the source, and do it with respect to the people and the culture. I am an ESL teacher and have lived in Indonesia (Sumatra) for a year and a half. I’m far from the garment industry (out here it’s palm oil farms), but perhaps it would be interesting for readers to know that even though there is a middle class in Indonesia, most people still are poor, and the cost of living is increasing. Earlier this year the government lifted some subsidies on fuel, and that has in turn driven up the price of food.

Many of my students cannot afford new clothes, so they, like so many others here, will often buy the used clothes in the weekly traditional markets. Those use clothes were manufactured in SE Asia for the Western market, worn by Americans or Europeans, then donated for secondhand, and somehow ended back in SE Asia. Last year it hit home when I encountered a pair of sweatpants with the WSU logo sewn on them at the market (I grew up in Eastern WA but lived in Seattle for 7 years before moving to Indonesia).

I think one of the big challenges for the future from the Indonesian side–not only for garment industry, but for mining and palm oil industries–is the amount of corruption infecting this country. Significant change may or may not happen depending on which person or business is benefiting, but that doesn’t mean we should stop trying.

I would love to have you do an article on the Family and consumer Science (FACSE)programs that you may have known as Home ec. that are still teaching sewing skills along with work skills to lead kids into a fashion career.I’m the FACSE Program supervisor at OSPI.