This fall we get to vote on an initiative that requires labeling of genetically modified foods. But it may not be an obvious choice.

Rides in the tractor were rare. Dusty and dirty, with the strong scent of rich soil, I remember running out to greet my dad in the field while he threshed a small plot of wheat, the remnants of what was once my grandpa’s farm in North Dakota.

My dad is a hobby farmer, and he has always had a different primary occupation. Being the sentimental type, he didn’t put a lot of thought into using anything but conventional seeds until I began my own research about genetically modified foods.

The topic has been an interesting connection point for the two of us as I’ve read about everything from farmer suicides in India over failed seeds and marches against Monsanto to increased yields and the potential application of GM technology to address food security and climate change.

It’s a global issue. And with this November’s Initiative 522 on genetically modified foods labeling, Washington residents have a chance to join the conversation about the role of technology in our food.

Washington’s proposed law could change the national tone toward the technology, which has implications ranging from international trade to development aid.

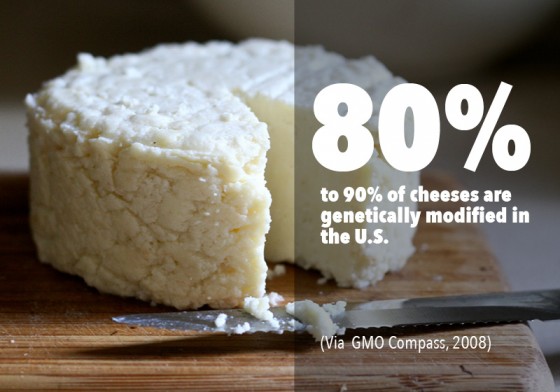

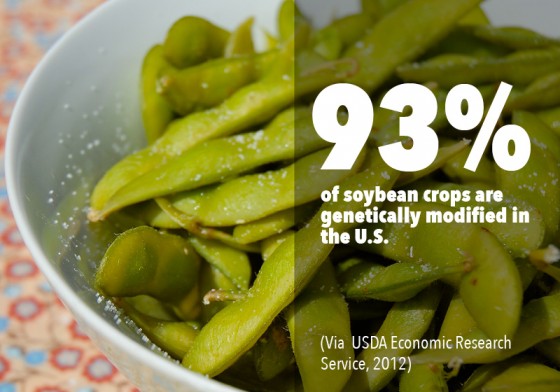

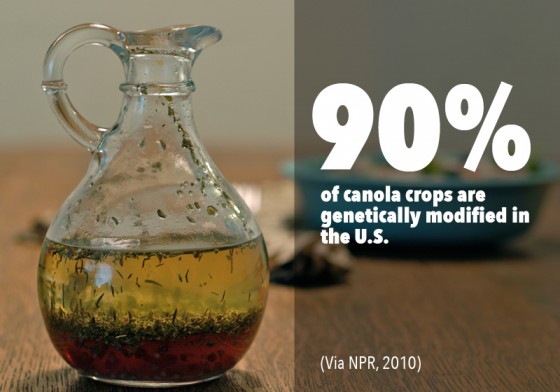

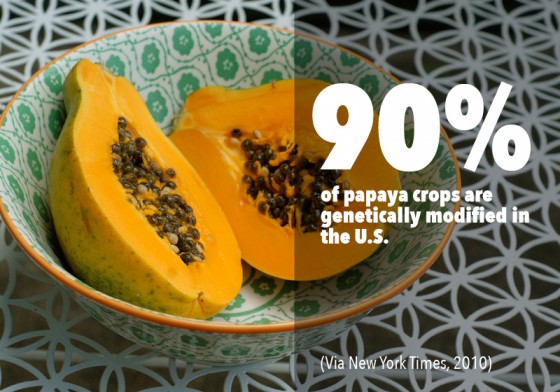

How much of your food contains GMO’s? Short answer: Almost all of it. (Photos by Rebecca Randall and flickr users Martin LaBar and Chiot’s Run)

So what does genetically modified actually mean?

Genetically modified organisms (commonly abbreviated as GMO or GM) are created using recombinant DNA technology, which was first done in plants in the 1990s.

Though humans have altered the genetic makeup of plants for centuries using traditional plant breeding techniques, biotechnology gives scientists the ability to breed seeds in a lab setting with genetic sequences from a different species to achieve a desired trait (i.e. soil bacteria that will kill specific pests).

Proponents hail the discovery for its ability to produce higher yields with less land and resources—something that is very appealing as the Earth’s population continues to grow rapidly.

Ever since then, there have been conflicting efforts to either stifle or encourage the use of genetically modified crops overseas.

Since the 90’s, U.S. policies allowed the advancement of the technology.

But recently there has been a swell of state efforts to label GM foods. Connecticut recently passed a labeling law, though its implementation is conditional upon other states also passing a similar law. Washington could certainly follow suit this November, thanks to a successful petitioning effort collecting over 350,000 voter signatures. The nation’s only other popular initiative, California’s Proposition 37, failed last November, gaining 47 percent of the votes.

What is I-522 all about?

Washington’s Initiative 522 would nearly mirror the European Union’s law, which went into effect in 2004. The law would require raw agricultural commodities, processed foods, seeds and seed stocks, if produced using genetic engineering, to be labeled when the GM content equals more than .9 percent of the total weight of the product.

“This initiative was really drafted on common global standards,” Elizabeth Larter, the spokeswoman for the Yes on 522 campaign told me.

There would be some exceptions: cheese, which often contains a genetically modified enzyme called rennet; dairy or meat products that come from animals that eat GM feed; and alcohol and food served by restaurants.

The No on 522 campaign says that the exemptions don’t make sense because some things that do contain GMO will still not be labeled under the new law.

Spokesman Brad Harwood said, “I-522 would mandate a costly and unnecessary food labeling requirement that doesn’t exist in any other state….If consumers are uncomfortable with GMOs there’s already an option to them, which is USDA-certified organic.”

Current USDA organic standards do not allow use of genetically modified seeds, but the certification also includes additional requirements regarding farming practices, such as prohibiting synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge and irradiation. In other words, all USDA organic labeled foods are GMO-free, but not all GMO-free foods are necessarily organic.

Opponents to Initiative 522 also include the Washington Farm Bureau, which is concerned about added complexity and cost to farmers who will likely need to keep more records and undergo testing, said Harwood.

“Most farmers love GMO crops because they’re more efficient, use less pesticide, and they have to plow their fields less often,” added Harwood.

Ironically, similar to last year’s marijuana legalization initiative, if passed, I-522 may technically be unenforceable under federal law. In May, U.S. legislators decided that states do not have the right to implement GM labeling laws.

However, legislators from Oregon and California spearheaded an attempt to require the federal Food and Drug Administration to label genetically modified foods. That bill has yet to move forward.

So are GMO foods actually dangerous?

Regulations about genetically modified foods aside (but please, don’t forget to vote), let’s consider the technology. Is this technology wrong? Is there a good way to use it?

Earlier this spring, I was sucked in by this video of a speech at Oxford University by Mark Lynas, an environmental activist and author, apologizing for the role he played in starting the global debate on genetically modified organisms.

Articulating it in an interesting, colorful way, he fully embraces organic farming and its benefits, while also coming out as a supporter of genetically modified foods. My mind was blown. These things haven’t typically gone together.

Mark Lynas talks about why he went from strongly opposing to supporting GMO’s.

As early as a 1992 Food and Drug Administration policy statement, the U.S. stance was not to label GM products because no genetic differences can be detected by taste, smell or other senses and no known allergens have been found.

Internationally, the U.S. has been the most open to the technology, while Europe has been a leader of the cautious approach. Concerns include impact on biodiversity, harm to non-crop-eating insects, such as butterflies or bees and increased use of pesticides.

Additionally, some strongly oppose the ability to own intellectual property rights for genetic technology, and the market dominance of only a few multinational corporations, such as Monsanto.

So far 64 countries have some sort of law requiring labeling of GMO foods.

A map of GM crops around the world in 2011. Newly industrialized countries like Brazil, India and China are embracing GMO’s. (Courtesy The Guardian)

Thresholds for the presence of GM in foods that triggers labeling vary from country to country: some are more lenient than the EU’s .9 percent. In South Korea it is 3 percent, while in Japan, it is 5 percent. In South Africa, food must be labeled if it is nutritionally different from conventional foods, but nothing has ever been found to be different.

While policies have focused on environmental effects of GM foods, critics also have health concerns. Though there certainly isn’t a lack of studies on health, conclusions vary depending, perhaps, on one’s faith in the unknown. While some interpret a lack of evidence that there are health issues as a green light for GM foods, others do not.

A number of reputable science organizations have concluded that there are no more health risks from GM foods than from conventional breeding, including the World Health Organization, the American Medical Association, and the British Royal Society. Also, a number of literature reviews have compiled data from multiple studies in one report, concluding that there are no health hazards.

However, there have also been alarming studies that received a lot of media attention, such as a study last November by French scientists in Food and Chemical Toxology Journal that concluded that rats fed Round-up ready maize experienced tumors and premature death.

Scary stuff.

As it turns out, whether or not GMOs are safe might not matter if no one wants to buy them.

Genetically modified wheat, which is not commercially available, was recently discovered growing in Oregon. Monsanto had done field trials in the area almost 10 years ago, on GM wheat that never made it to market. Now Japan and South Korea have cancelled their orders for U.S. wheat amid fears that it is contaminated, despite assurances from the USDA that it was an isolated incident.

Some developing countries, such as Zambia, have refused to accept U.S. food aid due to the high likelihood that it contains genetically modified seeds. The fear was that farmers would plant some of it and it would cross-pollinate with native varieties. Since Zambia exports its agricultural products to Europe, which is politically quite stringent about GMOs, there was a fear of losing its export market.

These are some examples of the issues that concern farmers, like my dad, despite what their actual views may be about the benefits of the technology.

But unlike my dad, many farmers depend on agriculture for their main source of income.

Enormous changes have come to American farming in the last century: technology ranging from my dad’s shiny new tractor to genetically altered seeds. While initially farmers made the choices about technology, now consumers want to have a say.

And since global environmental concerns such as climate change and loss of biodiversity affect the common good, we all must decide what role technology should play in the future of farming and our food system.

Are genetically modified organisms the right technology for the job?

Come November, we’ll see if Washingtonians think the good outweighs the bad.

An interesting review , but you left out a key point- the perversion of the technology by Monsanto etc, which is what many people object to. For example, the insertion of pesticide resistance genes into crops results in dependence on pesticides, which many people find disturbing.

Yes. I find it interesting that one of the most known uses of the technology is for pesticide resistance by companies like Monsanto that also sell pesticides (in fact rely quite heavily on that revenue). What do you think of insect resistant seeds (inserting a bacteria that is harmful to pests)? Usually studies show lower pesticide use with these seeds.

Who is Brad Harwood and why is he saying that most farmers want to grow GMO crops? Simply not true and he can sound like an authority.

Growing GMO crops simply increases the amount of herbicides sprayed on our precious fields and contaminating them. You need to know what the GMO modifications are: mostly Round-Up Ready and Bt. Why did the author imply that the US wheat supply is not based on GMO technologies? The particular strain of GMO in Oregon that was identified had not been marketed as human food. We need to look to science based evidence about GMO from other countries since Monsanto has restricted GMO testing in the US.